Now buckle up while I say the same thing again.

This paragraph is written on a college level. It was analyzed using a readability calculator that assigns a Flesch-Kincaid grade level equivalency and it scored a 14. Actually, it came in at 14.1, which is higher than the college and career readiness benchmark for graduating seniors, but rounding it down to 14 is adequate for our purposes. The remaining information in this paragraph addresses the importance of writing so family members understand your communications. While it is essential for educators to provide letters, documents, forms and tip sheets to parents, guardians and caregivers, while doing so they must remember to write at an appropriate level. If you compose these documents at a level which is too high for the average reader, you should realize that many family members will find it difficult to understand your message.

Do the above paragraphs basically say the same thing? Unfortunately, most school documents for families sound like the second paragraph. Research from the US Department of Education suggests up to 85% of parents may struggle to understand content written at that level.

We know how important it is for families to be 'involved,’ ‘engaged,’ or ‘empowered.’ We even know what type of parent involvement is most effective. Student performance increases when parents set high expectations and work on learning activities at home.

So why do parents struggle to do these two things?

In a previous blog post, I pointed out the need for schools to reconsider their tendency to only provide support to families via in-person events at school. Now it's time to look at how we can improve school-to-home written communications.

We’ve known for almost a century that the average reading level for adults in the United States is somewhere in the 7th-9th grade range. It fluctuates depending on the report you choose to believe.

Knowing many adults struggle to read and understand basic information, you would think schools would write content for parents at a reading level appropriate for the audience. Pull up your district or school website, read a Superintendent’s blog post, or check your school, district or state's ‘parent newsletter.’ You’ll probably find content that’s written at a college (or graduate school) level.

After reviewing thousands of school-to-home documents over the last two years I can safely say this is a systemic problem. Way too many documents for parents clock in with a grade level equivalancy which would be appropriate for a graduate school writing assignment.

Why are we writing at this level if parents struggle to understand it?

One disclaimer: Using ‘grade level equivalency’ (GLE) isn’t the most accurate way to discuss adult literacy levels, but it is easy to understand, so that’s what I’ll be using in this article. If you want a more in-depth understanding of adult literacy and how it’s measured, explore this page from US ED.

Here are a few examples of writing pieces created by educators, for parents:

The following paragraph comes from a tip sheet titled, “Is your child ready for reading in kindergarten?” It was created by a state department of education. Many schools and districts in the state are including it on their website, under ‘Helpful Links for Parents.’

“Early attempts and approximations at standard writing (often viewed as “just scribbles” by adults) are legitimate elements of literacy development. Children’s acquisition of writing typically follows general developmental stages, and individual children will become writers at different rates and through a variety of activities. Learning to write involves much more than learning to form alphabet letters.”

This opening statement is the first thing on the tip sheet, in the top left corner. Many parents will never read the helpful tips further down the sheet. They will give up after struggling to understand the first paragraph.

Ironically, the statement is found under the heading “Writing for a specific purpose and audience.” I’ll let you decide if the state DOE is doing that.

Here is how the section could be rewritten:

“Children move through stages as they learn to write. ‘Just scribbling’ is normal, and may be the first thing your child does. Some children will move through the stages quickly, and some may need more time. There are many activities you can do to help your child, but keep in mind not all activities help all children. Don't worry If an activity isn’t working for your child, just try something else. Learning to write is much more than writing ABC’s.”

GLE of revised paragraph: 4.9

Did the edits change the message, or does it essentially say the same thing?

The following sentence was found in an article about state accountability results. The purpose is to let families know how schools will use the data.

“Superintendents, school boards, principals, school-based decision-making councils and teachers must review and analyze the data to determine what instructional changes need to occur and which students may need additional interventions in order to be successful."

In all fairness, the entire article scored a 10.5 (still above the average reading level for adults), however, like many writing pieces we reviewed it includes pockets of language many parents will struggle to understand. The author is well meaning, but the article will fail to connect with most families.

Look at how that section could be re-written:

“Your child’s school and district will look at how each child performed on the test. The results help the school decide if they need to change the way they teach certain skills and concepts. The school will also use each child’s test scores to identify students who are struggling. Those students will get extra help at school.”

Grade level equivalency: 4.6

As it was originally written, we can estimate only 15% of parents would understand a sentence found in a “Parent Newsletter.”

I don’t envy Superintendent’s here in my home state of Kentucky. We’re a little too far north to completely avoid snow and ice, and a little too far south to do a good job of keeping the roads clear.

A few times each winter, district leaders must make a tough decision: “Should we cancel or delay school?”

They can keep school in session and hope children arrive safely, or they can cancel and field calls all morning from upset parents who don’t understand the decision. After all, “The road in front of my house is clear!”

Most districts try to head off upset parents by explaining their school closing policy. Here’s a sentence from a ‘inclement weather policy’ posted prominently on a district website:

“As early as 3:00 a.m., if snow, freezing rain, sleet or other dangerous precipitation presents [sic] our Director of Transportation and Deputy Superintendent/Chief Operations Officer set out to inspect the road conditions.”

The district probably hopes posting the policy will reduce the number of calls they get from upset parents when school is cancelled. I doubt it’s working. The reading level is too high.

To be fair, the entire policy is written at a 12.2 GLE, which is still too high, but here’s the big takeaway: Including this sentence near the beginning of the announcement will cause most parents to stop reading.

Here’s what that sentence could be:

“When we get snow, sleet or freezing rain, district leaders go out early to check the roads.”

GLE: 5.6

I ask again: Does the change in wording affect the overall message?

It's easy to pick apart the writing style of state and district administrators, but we make the same mistakes here at Bluegrass Learning. Our Family Five program is designed to teach parents how to support learning at home.

Here is an opening sentence from our print article about vocabulary development. It’s supposed to supplement a parent video on PreK language development.

“Numerous research studies have proven that a strong vocabulary directly impacts a person’s ability to understand and learn new information.”

The article is one of the first things we produced, and it is riddled with similar language throughout the entire piece. Thankfully, we’ve gotten much better.

As it was originally written, most parents won’t be able to understand our tips and suggestions. My huge intellect got in the way of actual communication (that’s a joke in case you were wondering).

Here’s a rough draft of how the sentence may sound when I’m finished editing:

“Many experts agree. When you have a strong vocabulary, it is much easier for you to learn new information.”

GLE: 6.7

While I have noticed senior administrators are more likely to write above the reading level of the average parent, many teachers also struggle. They do well with short, personal notes. As the writing pieces get longer, they revert to a style that would be more at home in a college class. We have found that many parents struggle to understand class newsletters and ‘beginning of year’ teacher letters.

I hire current and retired teachers to write video scripts for Family Five. Before they start writing I say:

“Remember, this is for parents…ALL parents. I don’t want an academic paper. Imagine you are sitting across the table and speaking with a parent who may not have a great education. Write in a conversational tone, in plain language. When you think you are finished with a lesson, read it out loud and ask: Is this how I would speak to a parent?”

While my directions are simple, you would be surprised to read the first drafts teachers submit. Almost without exception, they are dry, academic, and contain education jargon without any explanation of what the terms mean.

Thankfully, I hire great teachers who are open to feedback…and have a sense of humor. When they submit a script written at a high difficulty level, I hand it back and say, “Go ahead and hold on to this. It will feel right at home in your doctoral dissertation, but it’s not helpful for most parents. We need to make some changes.”

Writing plainly is easy, but it takes quite a bit of practice. Today, your style might be more appropriate for graduate level term papers, federal grant applications and operating procedures for your schools. You may be comfortable with that style, but if you want to reach more families you must learn to write plainly.

Here are steps you can take to ensure your school or district is sharing readable material:

1. Pick a readability calculator and learn how to use it.

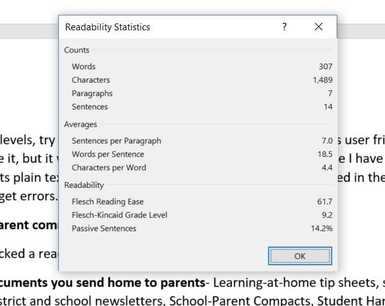

For ease-of-use, you can’t beat the Flesch-Kincaid analyzer built into Microsoft Word. Turn on the option in your settings and it will automatically calculate a score when you run ‘spell check.’ It allows you to easily check the entire document or just a selection, like a sentence or paragraph. The results will look like this:

Aim for an 8th grade reading level or lower. You might be surprised when you take a document currently written at an above college level, rewrite it in plain language (with no loss of meaning), and end up with a document on a 4th or 5th grade level. Reading it won’t prove to anybody how smart you are, but it will be something most parents can easily understand.

If you prefer Lexile levels, try the Lexile analyzer from Meta-Metrics. It’s not as user-friendly, and you must register to use it, but it will give you an accurate Lexile level. I have a couple of issues with the Lexile tool; It only accepts plain text files and you have to make sure the file is saved in the correct encoding (ASCII) or you may get errors.

2. Evaluate parent communications you already use:

Now that you’ve picked a readability tool, use it to evaluate:

| A. Printed documents you send home to parents- Learning-at-home tip sheets, school registration packets, district and school newsletters, School-Parent Compacts, Student Handbooks, etc. If it goes home to mom and dad, run it through the analyzer to see where you are today. If you are seeing 11th-12th grade levels and above, many parents will struggle to understand the document. B. Your website copy: Pay attention to the home page and your “Parents” page. They should be welcoming and easy to read. Here is an example of what to avoid (I don’t want to point fingers so district name has been changed). “Barnett County Public Schools recognizes that family and community engagement is essential as we partner to educate our students and prepare them for life-long learning. BCPS envisions a districtwide culture that promotes collaborative partnerships to support student learning, enrich educational experiences, and prepare students to excel as successful citizens in a global society. Once parents, teachers, and community members view one another as partners in education, a caring community forms around students, helping to ensure success.” GLE: 18.2 That’s the opening paragraph on the district’s ‘family and community’ page. My best guess? It’s helpful for school employees and 15% of the parents they serve. The remaining 85% of parents will find the district's ‘family page' too difficult to read. C. Downloadable docs and links on your website: I’ve seen quite a few schools and districts post “Helpful links for parents" that send families to external pages many parents will struggle to understand. A favorite in many districts is ASCD’s Lexicon of Learning, an online glossary of education terms. While you may think it will help parents understand education jargon, most of the definitions are written at a reading level way too high for the average parent. Their definition of ‘assessment’ is four paragraphs long. Here is the first: “Assessment: Measuring the learning and performance of students or teachers. Different types of assessment instruments include achievement tests, minimum competency tests, developmental screening tests, aptitude tests, observation instruments, performance tasks, and authentic assessments.” GLE: 19.8 The Prichard Committee for Academic Excellence, here in Kentucky, publishes a glossary. It’s not as detailed as the ASCD version, but it is much more parent-friendly. Their entire definition of ‘assessment’ is: “A test or evaluation of what a student knows and is able to do.” GLE: 5.8 While the ASCD definition is much more thorough, consider this: Why are you posting the link? If a parent doesn’t know what the word ‘assessment’ means, would it be more helpful to show them the ASCD definition, or the one from the Prichard Committee?  D. Your district and schools ‘Parent Engagement Policy:’ Forgive me for sounding like a parent complaining about school closures, but this one is a personal pet peeve. Too many parent engagement policies are nothing more than cut and pasted statements lifted from federal Title 1 requirements. Can you imagine anything less parent-friendly than legislative language? It says to me, and more importantly to your families, that you put zero thought into your plan and parent engagement is not a priority in your district. Take a long, hard look at the district and school policies. If they are written so the average parent can’t read and understand them, you are missing out on a valuable resource. It will be tough for families to provide input on improving parent engagement if they are unable to understand your policy as it’s currently written. E. Your district and school improvement plans: This is your opportunity to shine. Write them so most parents can easily understand your vision for the future. You can give more families a voice, and they might be able to provide unique viewpoints you haven’t considered. That’s only going to happen if parents find the plan easy to read. While writing this post, I pulled up a random district website and saw a link to their ‘Strategic Plan,’ right there on the homepage. Goal number one is deeper learning. Great! Let’s look at ‘Strategy 1.1.1,’ the very first thing they hope to do: “Adopt a broader definition of learning: Align teaching strategies, assessments, and rigorous learning opportunities that promote student mastery of academic knowledge and the development of the capacities (e.g., creativity, critical thinking, self-regulation) and dispositions (e.g., persistence, empathy, responsibility) necessary for success in life.” GLE: 24.3 Most parents will never read past the first strategy...because they can’t. For what it’s worth, here is how I would edit that statement: “Look at learning in new ways: We will look at how we teach students, how we test them, and how we give each child a chance to learn at high levels. We will make sure teaching, testing and learning are tied together. This will give students more than knowledge. They will learn social skills, coping skills and how to be creative, thoughtful, caring and persistent.” GLE: 5.6 It’s not perfect, but at least parents will be able to understand it. |

Writing simply isn't difficult. It’s just a shift in mindset and the use of plain language. When writing for parents, try this:

- Change ‘assessment’ to ‘test’

- Remove ‘Collaborate’ and replace with ‘work together’

- Change ‘stakeholders’ to ‘we’

- Change ‘administrator’ to ‘Principal’ or ‘leader’

- Stop using ‘Parents, guardians and caregivers’ and start using ‘families’

Break long compound sentences into two or three sentences. Drop the jargon and ask yourself the tough questions. Do you have to use the words ‘Tiers of Intervention’ when talking with families about RtI?

Try to find an alternative version of the 4 and 5 syllable words you use in more technical writing. Don’t get hung up on providing a ‘perfect’ explanation. Do they really need all those details?

When writing new pieces, frequently check your work with the readability tool to ensure you are on the right track. After a while it will become second nature.

If your district has a public relations staff, enlist their help, especially if you have former journalists. They know how to write about complex issues in very simple language, for an audience of average and below-average readers.

A few months ago I overheard something upsetting. I was presenting about parent engagement to a group of school Family Resource Coordinators here in Kentucky. After providing real-world examples of ‘tough to read’ school messages, I suggested they speak up when they see this happening at their school. One of the Coordinators muttered to her neighbor, “Yeah, like I’m really going to tell my principal he needs to change his writing style.”

This Coordinator’s entire job is supporting families, and she has decided not to suggest improvements because her principal might get upset. She learned something that could help children and families, and she’s not going to speak up because an adult coworker might get their feelings hurt.

That type of working environment should be unacceptable in any school. I hope it is unacceptable in your district.

No one likes to be criticized, but both parties should realize the suggestion is not a personal attack. It’s made from concern for students and families. We should strive to be kind in our suggestions and be open when others point out a way we can improve.

One final point to consider. The Flesch-Kincaid tool in Microsoft Word scored this article at an 8.4 (after removing all the ‘difficult to read’ examples). If you learned something from an article written at an 8th grade level, what will your families learn when you give them documents they can understand?

Author

Joe Deaton is Founder and President of Bluegrass Learning. He and his team have spent the last 4 years trying to answer the research question "Why do schools struggle to engage so many families."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed